Extending a Java test framework with plugins using the Service Provider Interface

Reading time: 4 minutes, 55 seconds

Sometimes, you have to look back to solve a problem. In this post, I will explain how I created a plugin based architecture for our end to end test framework using Java's 20 year old Service Provider Interface.

The problem

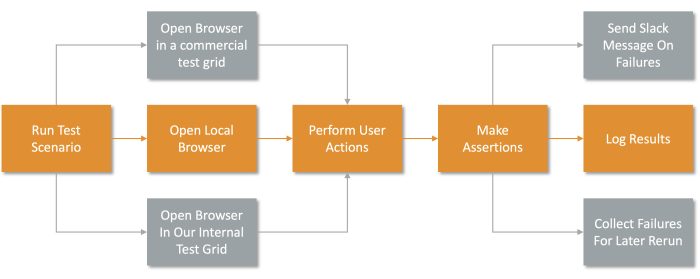

In the past, our internally developed UI end to end test framework "trupi" was pretty linear in nature. It would run a test, open a browser, perform some actions, assert some states and finally log the test result:

This was fairly basic and turned out not to be sufficient. More functionality was to be added, e.g. the ability to use remote browsers in different commercial or in-house test grids, slack messaging on failures and the collection of specific failures for a second rerun phase:

One potential and at first glance simple solution is to integrate all this functionality directly into the existing framework code. This approach has some drawbacks, though:

- The base framework would contain too much functionality that is not required for all use cases

- It would be tightly bound to specific browser hub vendors

- Anyone wanting to add or extend this functionality would need full framework code and architecture knowledge

- Every additional feature would cause a new framework release

The solution

After thinking about these disadvantages for a while, it was clear that this would not be the way to go. Instead, we wanted to have an easy to use plugin interface that allowed extending the framework without touching the base code.

The requirements were

- Writing a plugin should be really simple and each plugin should be a small separate Java project that can be maintained on its own

- New plugins should not require any change of the core framework

- Plugins should be managed and triggered by the core framework

- The plugin API should not interfere with the test framework's dependency injection

Service Provider Interface

In comes the Service Provider Interface (or "SPI"). This mechanism has been a part of core Java since JDK 1.3 as sun.misc.Service before it turned into javax.imageio.spi.ServiceRegistry in JDK 1.4 and finally changed again to java.util.ServiceLoader in JDK 1.6.

In a nutshell, it discovers and loads implementations on the class path that match a given interface.

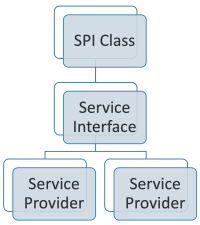

SPI consists of three components:

- Service Interface that providers need to implement

- Provider Registration API for registering implementations and giving clients access to them

- Service Access API which clients use to get access to service instances

Implementation

Each plugin can implement one or more interfaces that include one method contract each. For example, a plugin that should react to the webdriver being created would need the TrupiWebdriverCreatedAware interface:

package com.trivago.trupi.plugin.extension;

import org.openqa.selenium.WebDriver;

public interface TrupiWebDriverCreatedAware extends TrupiPlugin {

void handleWebDriverCreated(final WebDriver driver);

}You can see that every plugin interface extends the TrupiPlugin interface:

package com.trivago.trupi.plugin.extension;

public interface TrupiPlugin {

String getPluginName();

}This makes it possible to scan for all plugins by searching for matches against TrupiPlugin without having to specify every single derived interface.

A sample plugin using the above TrupiWebdriverCreatedAware interface could look like this:

package com.trivago.trupi.webdriver;

import com.trivago.trupi.plugin.extension.TrupiWebDriverCreatedAware;

import org.openqa.selenium.WebDriver;

public class WebdriverLogPlugin implements TrupiWebDriverCreatedAware {

@Override

public void handleWebDriverCreated(final WebDriver driver) {

System.out.println("The webdriver was created and I know about it now!");

}

@Override

public String getPluginName() {

return "WebdriverLogPlugin";

}

}In this example, it is supposed to write "The webdriver was created and I know about it now!" to the command line whenever the core test framework creates a new webdriver.

At this point, the plugin could not really be used though because it cannot be discovered yet by SPI.

Plugin discovery

Inside the core framework, the TrupiPluginLoader class finds all plugin jars that are currently on the classpath implementing the TrupiPlugin interface and stores them in a list. This list can later be used by the getMatchingPlugins method to call plugin methods of more specialized interfaces via reflection, like TrupiWebDriverCreatedAware.

package com.trivago.trupi.plugin;

import com.trivago.trupi.plugin.extension.TrupiPlugin;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

import java.util.ServiceLoader;

class TrupiPluginLoader {

private final List<TrupiPlugin> pluginList;

TrupiPluginLoader() {

pluginList = new ArrayList<>();

for (TrupiPlugin trupiPlugin : ServiceLoader.load(TrupiPlugin.class)) {

pluginList.add(trupiPlugin);

}

}

<T extends TrupiPlugin> List<T> getMatchingPlugins(final Class<T> requestedPluginInterface) {

List<T> matchingPlugins = new ArrayList<>();

for (TrupiPlugin trupiPlugin : pluginList) {

if (requestedPluginInterface.isAssignableFrom(trupiPlugin.getClass())) {

T plugin = requestedPluginInterface.cast(trupiPlugin);

matchingPlugins.add(plugin);

}

}

return matchingPlugins;

}

}

Plugin registration

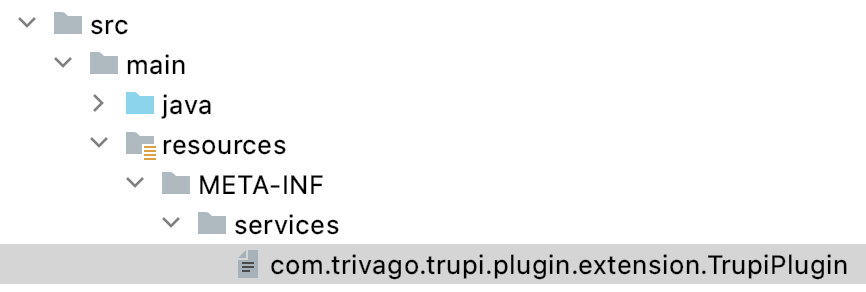

To make plugins discoverable via SPI, they have to implement known interfaces. Additionaly, they have to have a special file within their resources/META-INF/services folder that matches the package and name of the implemented interface:

In this case, the file is called com.trivago.trupi.plugin.extension.TrupiPlugin. The contents of this file is the package and class name of the plugin itself:

com.trivago.trupi.plugin.WebdriverLogPluginOnce this is in place, the plugin is discoverable through our TrupiPluginLoader!

Basic flow

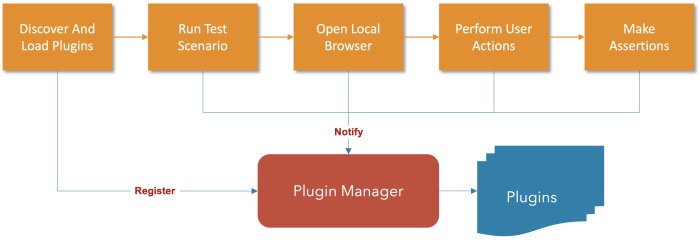

Once the test framework and the plugin jar are on the same classpath, this plugin is automatically discovered and added to the internal plugin list.

When the test framework creates a webdriver, it just needs to perform a search for the plugins that implement the TrupiWebDriverCreatedAware interface and invoke the handleWebDriverCreated method on them.

trupiPluginLoader.getMatchingPlugins(TrupiWebDriverCreatedAware.class)

.forEach(plugin -> plugin.handleWebDriverCreated(driver));At this point, out WebdriverLogPlugin plugin finally prints its message: "The webdriver was created and I know about it now!"

Conclusion

Using this architecture, we could reach our goal - a plugin API for our test framework that is losely coupled and is still flexible enough to fulfill all of our needs. This helped a lot with decluttering the code and reaching a cleaner architecture overall.

We don't only use it for external plugins but also started extracting out core framework functionality to "internal" plugins as this makes it much easier to work on code units without having to touch a lot of classes.

Note: I did not show the full implementation details here (plugin configuration, automatic activation and deactivation etc.) because this would have diluted the SPI explanation. If there is interest in those topics in the future, I will gladly write another blog post about it!